thinking about the narrator

As a certified Amherst Writers and Artists workshop facilitator, I use this structure for all of my writing workshops:

As a certified Amherst Writers and Artists workshop facilitator, I use this structure for all of my writing workshops:1) keep all writing offered in the workshops confidential

2) offer exercises as suggestions

3) remind folks that sharing is optional

4) respond to all writing as though it's fiction and with what we liked/found strong

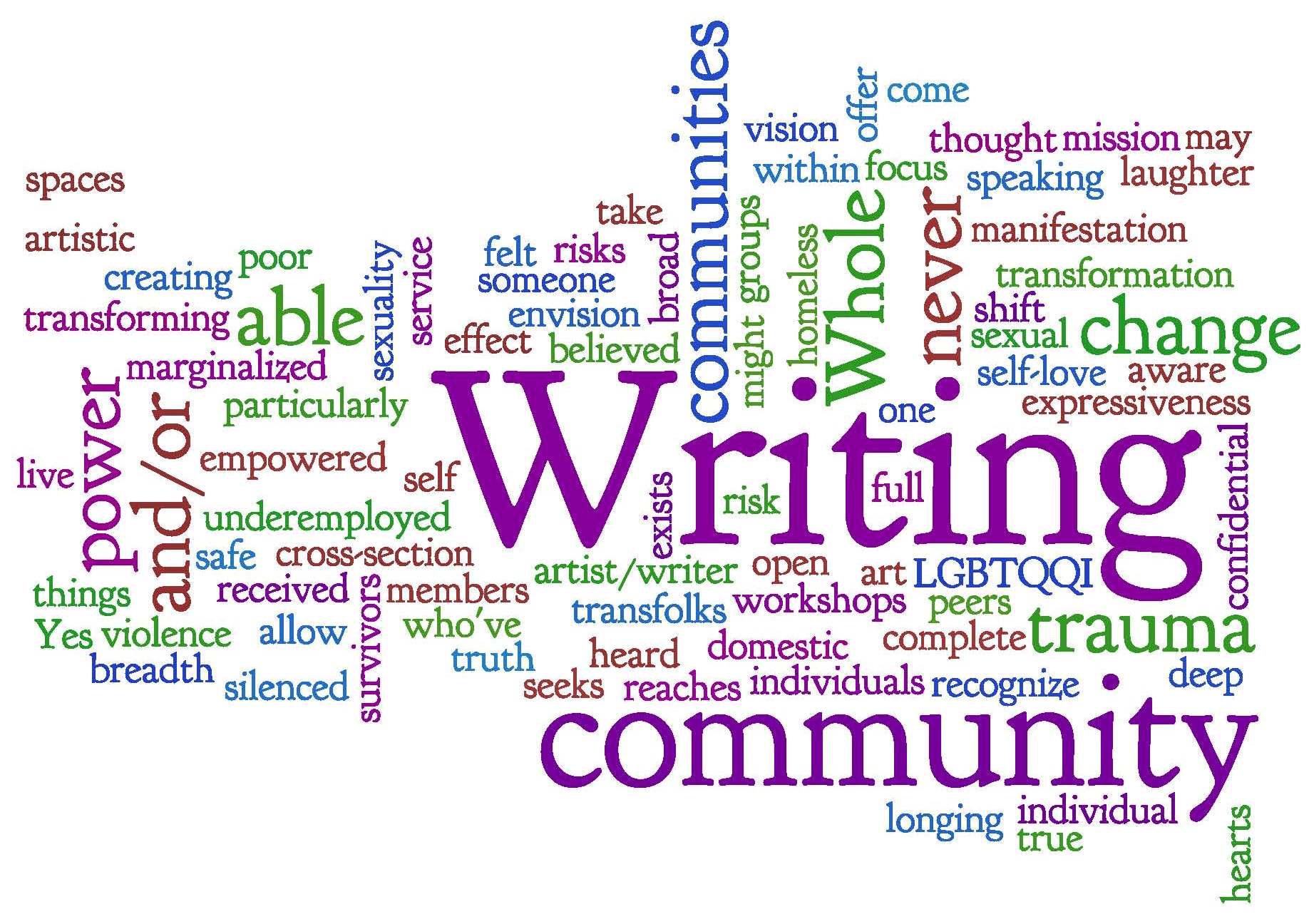

Now, the Writing Ourselves Whole workshops that I facilitate (survivors writing workshops and erotic writing workshops) often end up, at least for many (but not all!) participants, being 'life writing' opportunities workshops, where the writing is a telling of our own stories, getting into that thick truth of the everyday stories we exist within.

As a facilitator (and as a writer) I am interested in making/having opportunities for us to tell the whole truth(s) and so at first when I am going through the Amherst Writers and Artists (AWA) practices with a new group, I describe the way the method holds space for all this openness: you get to write whatever you want here because we keep it all confidential, and you get to do the exercise or not do the exercise whatever you want, you can even write about how much you hate the exercise and you can read it or not and if you read we only say what we like and what’s strong...

and then scratch screech wham I feel like I’m pulling on the breaks around all that freedom (although that's not the case). The piece that can be the most challenging for folks new to the AWA method is the part where we talk about all the writing as though it’s fiction. Unless instructed otherwise by the writer, we talk about the narrator and the characters in the piece (rather than saying 'you' to indicate that the writer and the one written about is necessarily the same).

and then scratch screech wham I feel like I’m pulling on the breaks around all that freedom (although that's not the case). The piece that can be the most challenging for folks new to the AWA method is the part where we talk about all the writing as though it’s fiction. Unless instructed otherwise by the writer, we talk about the narrator and the characters in the piece (rather than saying 'you' to indicate that the writer and the one written about is necessarily the same). Initially, this can feel like a confusing irritation. I sense folks cringing under the weight of one more thing to remember and how do you talk about fiction anyway what if I do this part wrong?>

I take a deep breath. I say, this is how we talk about it – we don’t know what’s fiction and what’s nonfiction – we don’t need to know.

This is what I want to talk about: the wording matters. How we talk about something matters.

This is what I want to talk about: the wording matters. How we talk about something matters. There’s a space enacted when I talk about your story in the 3rd person; there’s a different intimacy, in a way: slightly less immediacy, more distance, which, when we’re handling something raw and electrified like brand new writing is a good and useful thing.

We offer each other risky stories in these workshops – and in most writing spaces. We need to be tender with each other in response. This guideline is part of the tenderness, the way we set a structure that creates a space for enormous risk: we won’t tear it down, and we won’t tie it to you. We won’t point at you while we are talking about it.

Here’s the other thing that happens – if we have made fiction with our stories, suddenly we are strung up on the line of It All Has To Be True when someone refers to the “you” from the story as fact we all know there is a difference between facts and truth…

One more thing? Talking about the piece of writing as though it's fiction gives us as peer writers and respondents the chance to forefront and acknowledge our lenses. There’s room for each of our interpretations. If I have written a story about some situation between, say, my sister and I, and to many people it sounds sad and I am trying to find language for the joy in a difficult moment, response to that piece will likely run a gamut from “I felt the happiness they got to have at that difficult time” to “they were so sad and that was really strong for me, came through really clearly.” When someone 'misinterprets' me when I am speaking, especially in response to something intimate or personal or painful, and I feel the need to clarify, to correct. Within this structure, though, I have the freedom (the gift!) of hearing multiple interpretations of my telling – I get to hear multiple readers’ responses, what they hear in my writing, what they bring, too, to their hearing. I don’t have to take it personally – it reminds me that every reader (including editors – and friends/lovers/parents!) have a lens, bring what they’ve experienced to a story.

There’s a working space that gets opened up around us when one person puts her words in the room and then all of us, the writer included, gets to look at those words as a bit detached from the writer herself. We get to turn the story over, allow response to all of its angles, aspects, curves, undersides. Often, I picture the story as a silvery-malachite ball floating next to the writer: we all get to enjoy this creation for what it is, exactly as it is, expecting nothing more from it (even if we didn’t want it to end while we were listening).

There’s a working space that gets opened up around us when one person puts her words in the room and then all of us, the writer included, gets to look at those words as a bit detached from the writer herself. We get to turn the story over, allow response to all of its angles, aspects, curves, undersides. Often, I picture the story as a silvery-malachite ball floating next to the writer: we all get to enjoy this creation for what it is, exactly as it is, expecting nothing more from it (even if we didn’t want it to end while we were listening).For me as a human subject, it’s difficult to be examined, responded to this way – I get a little prickly and nervous, even if all the feedback and words I hear I know are supposed to be ‘good’ and strong – still there’s a discomfort, more

In a way, talking about the new writing as fiction objectifies the work in the best way, highlights its status as an artistic creation as opposed to a confession, and allows us as writers and as listeners to experience the distance between who we are and how we tell it; this part of the structure also holds the separation between writing group and therapy group. These workshops are not therapy groups. We are creating art while we put language to difficult or new or exciting or scary or sexy or socially-unacceptable truths.

What happens in that in-between space, the transformation of memory and fantasy into words and onto paper, is sacred, and talking about a work as though it’s fiction protects and honors that space and that artistry in all of us.

Your turn: How is it for you, if you've participated in an AWA workshop or facilitated such a space -- what's your experience of the 'fiction' part of our practice?

Labels: AWA, fiction, transformative writing, writing ourselves whole, writing process

This is such a big question – I actually feel I need to break it down into two:

This is such a big question – I actually feel I need to break it down into two:

On the one hand, I think anyone ought to be able to do this work. I think to myself, Look, I haven’t had any special training and I did it. I don’t have an MSW or experience as a therapist. But here’s what I do have: personal experience of surviving sexual abuse; training and experience as a volunteer listener for youth and battered women and men; certification as an Amherst Artists and Writers writing workshop facilitator; training as a crisis/peer support group facilitator. All of these skills came in handy during the writing groups I’ve facilitated.

On the one hand, I think anyone ought to be able to do this work. I think to myself, Look, I haven’t had any special training and I did it. I don’t have an MSW or experience as a therapist. But here’s what I do have: personal experience of surviving sexual abuse; training and experience as a volunteer listener for youth and battered women and men; certification as an Amherst Artists and Writers writing workshop facilitator; training as a crisis/peer support group facilitator. All of these skills came in handy during the writing groups I’ve facilitated.

In a transformative writing group, one thing (among others) folks seem to want, as survivors and particularly as writers, is a hearing. That’s what these groups can offer. The original AWA training, for example, helps you acquire a sense of how not to be blown away by heavy, hard, overwhelming emotions; how to ride through hard high intense roller coaster rides of emotion without getting thrown off or shutting down. Most times, you don’t need to do anything but listen, deeply hear and experience the words as they are offered to the group, and to give your personal individual feedback about the writing itself, while modeling for others how to do the same.

In a transformative writing group, one thing (among others) folks seem to want, as survivors and particularly as writers, is a hearing. That’s what these groups can offer. The original AWA training, for example, helps you acquire a sense of how not to be blown away by heavy, hard, overwhelming emotions; how to ride through hard high intense roller coaster rides of emotion without getting thrown off or shutting down. Most times, you don’t need to do anything but listen, deeply hear and experience the words as they are offered to the group, and to give your personal individual feedback about the writing itself, while modeling for others how to do the same.

Yes, I absolutely believe art can heal. Why? Because it has done so for me, and I watch it work for others.

Yes, I absolutely believe art can heal. Why? Because it has done so for me, and I watch it work for others.

When finding a way to express difficult or marginally-socially-acceptable things (such as sexual trauma or sexual longing), art (its creation and its very existence!) heals in that it provides outlet and inlet, deep risk and safety, camouflage and exposure: it is large, contradicts, contains multitudes, just like us, as

When finding a way to express difficult or marginally-socially-acceptable things (such as sexual trauma or sexual longing), art (its creation and its very existence!) heals in that it provides outlet and inlet, deep risk and safety, camouflage and exposure: it is large, contradicts, contains multitudes, just like us, as  Transformative writing is writing that changes you in the process of its creation. A dictionary gives one definition of transform as “to change completely for the better.” Another definition: “to convert one form of energy to another.”

Transformative writing is writing that changes you in the process of its creation. A dictionary gives one definition of transform as “to change completely for the better.” Another definition: “to convert one form of energy to another.”

I’m talking about the fact that the process of writing itself can be an erotic experience, if we can engage a definition of “erotic” that’s closer to Audre Lorde’s (“I speak of the erotic as the deepest life force, a force which moves us toward living in a fundamental way. And when I say living I mean it as that force which moves us toward what will accomplish real positive change.”

I’m talking about the fact that the process of writing itself can be an erotic experience, if we can engage a definition of “erotic” that’s closer to Audre Lorde’s (“I speak of the erotic as the deepest life force, a force which moves us toward living in a fundamental way. And when I say living I mean it as that force which moves us toward what will accomplish real positive change.”